There is no shortage of active disk jockeys in most good-sized American

cities, but among popular-music aficionados, there is only one per city who

is really the man, the No. 1 cat. He may not have the greatest number of

listeners and his may be one of the smaller stations, but he is the only

one who digs, who really knows. In Miami, the man is Butterball; in Baltimore,

Fat Daddy; and in Allentown, Pa., you have to give it to Frantic Freddy.

For a number of years the fastest rock-'n'-roll gun in New York City was

B. Mitchell Reed (Big B.M.R.), and in Philadelphia today -- known as a "Break-out

Town" for new rock-'n'-roll songs and dances -- all the marbles belong to a

remarkable young 24-year-old named Jerry Blavat, the "Geator with the Heater,"

the "Boss with the Hot Sauce." Typically, his 1,000-watt station, WCAM, is

puny alongside some of the Philadelphia giants . . . .

But there are 500,000 teenagers in a 15-square-mile area of Philadelphia

who manage to tune in on him and would gladly form platoons and follow the

Geator in a triple-time Bug-A-Loo all the way to Upper Volta if he so much

as suggested that's where the action was. There is no shortage of active disk jockeys in most good-sized American

cities, but among popular-music aficionados, there is only one per city who

is really the man, the No. 1 cat. He may not have the greatest number of

listeners and his may be one of the smaller stations, but he is the only

one who digs, who really knows. In Miami, the man is Butterball; in Baltimore,

Fat Daddy; and in Allentown, Pa., you have to give it to Frantic Freddy.

For a number of years the fastest rock-'n'-roll gun in New York City was

B. Mitchell Reed (Big B.M.R.), and in Philadelphia today -- known as a "Break-out

Town" for new rock-'n'-roll songs and dances -- all the marbles belong to a

remarkable young 24-year-old named Jerry Blavat, the "Geator with the Heater,"

the "Boss with the Hot Sauce." Typically, his 1,000-watt station, WCAM, is

puny alongside some of the Philadelphia giants . . . .

But there are 500,000 teenagers in a 15-square-mile area of Philadelphia

who manage to tune in on him and would gladly form platoons and follow the

Geator in a triple-time Bug-A-Loo all the way to Upper Volta if he so much

as suggested that's where the action was.

His radio show was on WHAT in Philadelphia when I met him, but a couple of weeks ago he switched to WCAM, which is in nearby Camden, N.J., and serves the same area. The reason he switched was that WHAT wanted him to broadcast live instead of on tape, and that would have interfered with his record hops.

The kids buy it, and the proof is that when another deejay slips into this pattern, the kids stone him to death.

One of the Geator's new acquisitions is a public-relations expert named Warren Weiner, a worried-looking fellow of indeterminate age, who picked me up in a rainstorm at the Philadelphia train station . . . He said that the Geator was taping a TV show ... "His relationship with the kids is beautiful. It's no longer enough to be a deejay with a pretty face. You must be involved with them and speak their lingo. They want themselves up there and that's Jer." Weiner explained that the Philadelphia kids had rejected a go-go style and invented their own dances, the Slow Fizz, the Twist, the Philly Dog, the Discophonic Walk."

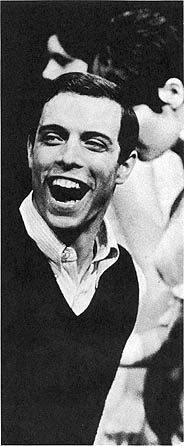

On the sound stage, the Geator was standing in a group of teenagers he uses as dancers on his TV show, and for a few minutes it was hard to pick him out of the crowd. . . . The Geator came forward and introduced himself, an appealing young man with a warm smile . . . .

We took a coffee break. . . . At the table the Geator seemed anxious to block out the TV show and talk about radio. He said he had built his show by digging out Oldies that had never made it, with sayings such as "Fresh from the hot heater" (car heater), by standing firm against format radio, and most of all by sensing the special musical appetite of the hip Philadelphia teenagers . "If I don't dig it," the Geator said, "it could be my father out there grooving on the record and I won't play it." It had been hell during the Beatle reign, when there had been much pressure to get on the bandwagon. "But I sensed that it just didn't have enough soul for my kids. The Stones, yes, the Beatles, no. So I'd go up to Fonzo's Restaurant and the upper-class kids would say how come no Beatles and I'd say it's just not my schticklach, not my groove, not for my kids. So I finally gave in and played a few, and I got bombarded by phone calls saying 'Geator, what you doing, man?" . . . "Where the re-action is" might very well serve as his slogan," said Warren Weiner.

A cluster of new teenagers, released from school, had washed into the studio, some to dance with the Geator on the show and others to sit in the audience. . . . For some mysterious reason, the favorite rock-'n'-roll dances in Philadelphia are not those solitary non-connected affairs you see on both coasts, but rather the "line" dances in which great groups of kids line up in formations to dance in a military-communal style. The Geator organized a few of these, was swallowed up in them; and although they were far from precise in their execution, they struck me as being more fun to watch than the more professional Shindig- and Hullabaloo-style dances.

I talked to some of the teenagers in the audience who said they liked the Geator because (1) he was rich, yet didn't wear fancy clothes; (2) he was really one of them; (3) you could really call him if you were in trouble; (4) he really knew what it was like; (5) he was much better than their folks to talk to; and (6) he stood up against the English thing.

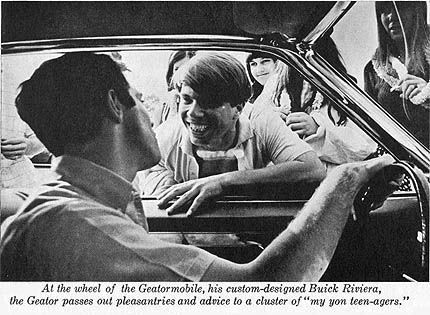

After dinner we drove to Station WHAT so that the Geator could do his nightly deejay show. . . ."What has the Geator got?" he asked a few teenagers who'd hitched a ride with us. "You're with us," they said in chorus. . . . "Keep rockin'," he hollered to some ladies in an adjoining car, " 'cause you only rock once." . . .

Philadelphia seems to have a rock-'n'- roll, teen-dance heritage that no other city has. Fourteen years ago there was a radio program called the 950 Show which was the first in the country to invite kids to come down and dance in the studio. This turned into the WFIL-TV Bandstand (Bob Horn) -- the first TV teen-disk dance show in the country, which in turn slid into the famous Dick Clark American Bandstand, originating, once again, in Philadelphia. At the time of the Dick Clark and Bob Horn shows, the whole record-industry apparatus was wired into Philadelphia. At any given time, half of the people in the record business could be found in their permanent hotel suites there, trying to get their records pushed. There was a kind of momentum established that continues to this day. A Philadelphia record or dance will always be given some sort of an edge in the record business, I'm told. . . . Even though the Clay Cole-Thaxton-style show is now on the wane all over the country, Philadelphia still has six teen-TV dance shows, competing ones, which is the most in the country. On Saturdays you can go nonstop with these shows from noon to seven at night. Every week the Geator listens to 200 new records which are mailed to him by distributors, manufacturers, often by new and untried groups trying to break in. Because of copyright dangers, he will not play an "amateur dub" but in at least one case, that of There's a Moon Out Tonight by the Capris, he sent an untested arrangement to a record promoter in New York, and it made the top ten in the country. He listens to the week's new records on Saturday nights and feels he can tell after 20 seconds at the most whether it's for him and for his audience. Getting four playable ones out of the 200 is considered a good haul. If his taste has any bias, it is strongly in the direction of rhythm and blues-which puts him in line, at least for the moment, with the only discernible current trend in popular music. At WHAT the Geator slipped behind a microphone, sat in his deejay's chair and seemed more comfortable than he had all day. All wedged in by piles of records, he closed his eyes, and somehow made his face shine. It was a Catholic-school holiday, and he asked the Catholic schools how it felt to have a day off and then quickly told the public schools not to worry their cotton-pickin' heads because they'd be getting one, too. Then he played rhythm-and-blues records, . . . many of them obscure tunes by fringe groups that somehow had got big around Philadelphia and never amounted to much nationally. During the rhythm sections, he talked over the records, doing little ecstatic woofs and cries, inviting listeners to take their dancin' feet to his record hop the next night at Chez Vous -- and while they were at it, to open a teen charge account at Berg Brothers. A Temptations record ("If I have to cry to keep you, I don't mind weepin' ") slipped off the track and began repeating, and he punched himself, saying. "There goes the goddamned mood," but he recovered and read a letter from a fan who wanted to get started as a deejay himself. "Go learn a board," the Geator advised, meaning a control board, "practice selling products from the ingredients on bottles, and most of all, babe, never lose your desire." "That's soul," he whispered to me, during Sweet Thing by the Spinners. "I may not be the best jock in the world, but I've got my own built-in excitement meter."

"What you've just seen" [said Warren Weiner,] "is a rebel against the system."

After the hop we took a ride back to the TV station where the Geator would witness the final editing of his weekly TV show. . . . At the TV station the Geator ordered baked hoagies and beer for all.

At four in the morning the Geator's show was finally completed. At the Marriott Motel we had some steak and eggs and were joined by a group of prom kids from Roxborough High, joking about their school's publicized drug-addiction problem, but actually a little downcast about it. The Geator told them it was nothing to joke about, but that they would weather it through and that Roxborough was still the greatest. They seemed cheered by this insight and thanked the Geator as they left, saying, "We can really talk to you." Then we were joined by a boy who really gave the Geator a chance to show what his patter could accomplish. The boy had swallowed enough bennies to fill the emergency ward at Lenox Hill; his eyes were half out of his head. He was a wealthy kid and his idea was to get into his Ferrari and shoot down to the Jersey shore to watch the sun come up. He had about as much chance of driving half a mile as I'd have flying a trolley car to Neptune. The Geator let him wise off, insult everyone at the restaurant counter, and then spoke to him . . . . The fuzz were out, all over the highway. Checking every car for boozers. The really hip thing was to say you went to Jersey, not actually go. Yeah, the kid said, that was the really hip thing. He walked home, went to bed, and it seemed likely that the Geator had kept him from killing himself. After the Ferrari kid left, a stout man named Buddy Nolan took a seat at the counter and turned out to be James Brown's road manager. Nolan brought regards from James Brown, and both agreed that Brown had given the performance of his life on the Geator's show, much better than his work on the Ed Sullivan telecast . . . . They talked for hours about great deejays of the past, and when there was nothing left of the night, Nolan told the Geator . . . every town had only one cat, and in Philly, "You the man, babe." The Geator chewed on that awhile, decided it made sense and then thought it would be a good idea to go home and get some sleep.

|

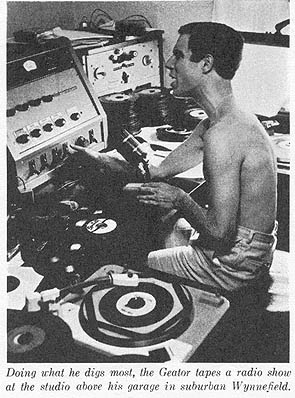

The "honest foundation"

for the Geator is his radio deejay show, and it is above his Wynnefield garage

(where he often prerecords his broadcast) or wedged inside a castle of records

at the station that he seems most comfortable. In his seat he does the Wagner

Walk or the Boomerang or one of the other new Philly dances; his eyes glaze

over, he makes sensual faces, strange, woofing, barking, jungle "soul" cries,

and for two to four hours he "feels" his teen-age audience, feeding them

two from the fast pile, one from the slow, sometimes vice versa, guiding

their mood as though he were at the controls of a giant, swinging, teen-age

bomber. All talk on the show must have a beat ("Kings and queens, yon royal

teens, this is your Geator with the Heater coming to you on Big-Tahm Thursday

where we rock the big tick- tock, where we got the class to beat all of the

blast from the past") right down to the commercials ("Pick up your heels,

pick up on wheels ... at Bob-O-Phonic Bob Zimmerman's Used Car Emporium.

. . . ") and so closely is the Geator tied to his control board, so firmly

is his style hooked into the Big Beat that you begin to think of him after

a while as just another rocking, grooving stereo component. He built the

show by regularly playing Oldies (records which at one time or another were

on the best-seller charts), by playing the "flip" sides of many hits (which

turned out to be better than the hits), by tuning himself in to the musical

taste of Philly teenagers which, for some reason, is a little different from

that of other teenagers (there's never been that much admiration for the

Beatles, for example), and in some way getting himself accepted by the teenagers

as a peaceful, trustworthy emissary from the adult world. (When a Philadelphia

teenager runs away from home, becomes pregnant, gets busted by the fuzz,

his or her first phone call will often enough be to the Geator.) He talks

effectively over records (an insufferable practice when tried by other jockeys),

has fought a one-man crusade against format radio (that style of broadcast

in which you simply do your jingles, sports, and play records from the Top

40). His main thrust has been the delivery of advice to teen-agers on love

(take the good with the bad) and growing up (you are what the cat above made

you, man) which is bone-chillingly clichéd but recognizes that to be a

teen-ager at all is to be, by definition, a living cliché, and that

any kind of recognition at all, from the adult world, is priceless nectar.

The "honest foundation"

for the Geator is his radio deejay show, and it is above his Wynnefield garage

(where he often prerecords his broadcast) or wedged inside a castle of records

at the station that he seems most comfortable. In his seat he does the Wagner

Walk or the Boomerang or one of the other new Philly dances; his eyes glaze

over, he makes sensual faces, strange, woofing, barking, jungle "soul" cries,

and for two to four hours he "feels" his teen-age audience, feeding them

two from the fast pile, one from the slow, sometimes vice versa, guiding

their mood as though he were at the controls of a giant, swinging, teen-age

bomber. All talk on the show must have a beat ("Kings and queens, yon royal

teens, this is your Geator with the Heater coming to you on Big-Tahm Thursday

where we rock the big tick- tock, where we got the class to beat all of the

blast from the past") right down to the commercials ("Pick up your heels,

pick up on wheels ... at Bob-O-Phonic Bob Zimmerman's Used Car Emporium.

. . . ") and so closely is the Geator tied to his control board, so firmly

is his style hooked into the Big Beat that you begin to think of him after

a while as just another rocking, grooving stereo component. He built the

show by regularly playing Oldies (records which at one time or another were

on the best-seller charts), by playing the "flip" sides of many hits (which

turned out to be better than the hits), by tuning himself in to the musical

taste of Philly teenagers which, for some reason, is a little different from

that of other teenagers (there's never been that much admiration for the

Beatles, for example), and in some way getting himself accepted by the teenagers

as a peaceful, trustworthy emissary from the adult world. (When a Philadelphia

teenager runs away from home, becomes pregnant, gets busted by the fuzz,

his or her first phone call will often enough be to the Geator.) He talks

effectively over records (an insufferable practice when tried by other jockeys),

has fought a one-man crusade against format radio (that style of broadcast

in which you simply do your jingles, sports, and play records from the Top

40). His main thrust has been the delivery of advice to teen-agers on love

(take the good with the bad) and growing up (you are what the cat above made

you, man) which is bone-chillingly clichéd but recognizes that to be a

teen-ager at all is to be, by definition, a living cliché, and that

any kind of recognition at all, from the adult world, is priceless nectar.

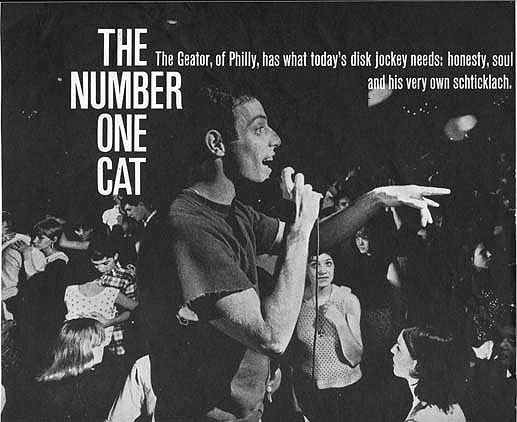

[The next] evening I

attended one of the Geator's record hops. Some 1,500 to 2,000 teenagers

show up at each one, paying a one dollar admission, and the Geator will run

as many as six in a single weekend. . . . As we approached

the ballroom, its very windows seemed to bulge with music and generalized

pandemonium. . . . The hops last two hours, during which time the Geator

plays only "hop" records, ones that are a little too jumpy and raucous for

radio and TV. Shortnin' Bread by the Blisters and Bila by the

Versitones are examples. The Geator introduces the records from a small

stage and then dances with as many as 15 teen-age girls during one number.

They compete hungrily to get on-stage with him, one girl doing her

little bit and then, seconds later, being banged on the shoulder by the next

eager performer. The teenagers seem starved for heroes, eager to applaud

almost anything. The Geator introduced me, asked me a question which

I did not hear; I answered "sensational," the first word that came to mind,

and was almost borne aloft on dancing shoulders, a new teen-age idol.

[The next] evening I

attended one of the Geator's record hops. Some 1,500 to 2,000 teenagers

show up at each one, paying a one dollar admission, and the Geator will run

as many as six in a single weekend. . . . As we approached

the ballroom, its very windows seemed to bulge with music and generalized

pandemonium. . . . The hops last two hours, during which time the Geator

plays only "hop" records, ones that are a little too jumpy and raucous for

radio and TV. Shortnin' Bread by the Blisters and Bila by the

Versitones are examples. The Geator introduces the records from a small

stage and then dances with as many as 15 teen-age girls during one number.

They compete hungrily to get on-stage with him, one girl doing her

little bit and then, seconds later, being banged on the shoulder by the next

eager performer. The teenagers seem starved for heroes, eager to applaud

almost anything. The Geator introduced me, asked me a question which

I did not hear; I answered "sensational," the first word that came to mind,

and was almost borne aloft on dancing shoulders, a new teen-age idol.